The Arrival of John Clark: A Permanent City is Born

The Bluff That Became a Town

Before St. Andrews was a place you could point to on a map with confidence, it was more like an idea than a town.

This shoreline was known. Used. Worked. But not settled in the way we think of settlement. A few people came and went with the seasons—fishing, salting, trading when it made sense, then disappearing back into the wider world when it didn’t. The bay was a pantry and a safe harbor, not a hometown. No streets to speak of. No town center. No “main corner.” Just camps and scattered lives, tied to tides and weather more than anything written in a courthouse ledger.

Then, in the late 1820s, a man with a national reputation stepped off the page of politics and onto the quiet edge of this bay.

And St. Andrews changed from “somewhere” to here.

The World That Pushed Clark South

John Clark’s move to St. Andrews didn’t happen in isolation. In the early 1820s, Florida had only just become U.S. territory (it became a state in 1845), and the federal government was working to stabilize and control its newest coastline. That work depended on experienced, trusted men—former military leaders, governors, and political operators who knew how to impose order on the frontier. Clark fit that mold exactly. His arrival at St. Andrews was as much about timing and national need as personal choice.

A Nation Rethinking Growth

The country Clark left behind had just been shaken by the Panic of 1819, the young nation’s first major economic crash. Easy money had dried up, land speculation collapsed, and confidence gave way to caution. In that climate, practical places mattered—harbors, food sources, timber, and land that could sustain real work. St. Andrews Bay offered those fundamentals. Clark’s decision to build here reflected a broader shift toward permanence over speculation.

Expansion, Limits, and Reality

The South was still expanding, pushing settlement outward and tying new communities to land, labor, and production. Clark brought that mindset with him, but Florida’s frontier imposed limits. Growth would be slow, shaped by isolation, conflict, and thin infrastructure. He could give St. Andrews roots—but not instant prosperity.

Why His Timing Mattered

National interest in coastal resources and harbors gave St. Andrews significance beyond its size. Clark’s presence signaled that this bay was no longer just a seasonal stopping place. After his death, those same national forces carried St. Andrews forward—and later pulled it into the disruptions of the Civil War era. What endured was the permanence Clark helped establish: St. Andrews was no longer a camp on the bay. It was a town, solid enough to survive what came next.

Before Clark: A Bay With Visitors, Not Neighbors

St. Andrews Bay had always offered what the coast still offers today: protection from storms, an easy place to anchor, fish in the water, and a breeze that makes the heat livable. People knew that long before any town existed.

But knowing a place and building a life in it are two different things.

In the 1820s, what we now call St. Andrews was mostly seasonal use—small groups camping and working, especially along the waterfront, doing what coastal people have always done: fish, salt, mend nets, trade a little, move on. The bay was useful, but it wasn’t yet a community with staying power.

That’s the difference John Clark made. He didn’t just use St. Andrews Bay.

He committed to it.

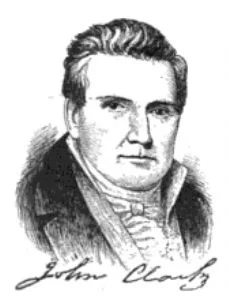

The Man Who Had Already Been Somebody

John Clark didn’t arrive here as a hopeful drifter or a broke adventurer. He came as a man who had already lived several lifetimes in one.

He had served in the Revolutionary War, risen in influence and responsibility, and eventually became Governor of Georgia. That matters, not as a résumé line, but because it tells you what kind of man he was: experienced at decision-making, power, logistics, people, and long-term planning.

He was eventually caught up in the contentious political strife in Georgia in the early 1820’s and underwent a rise and fall in favor, as happens in politics. And after the noise and combat of public life, he did what a lot of strong-willed leaders do when they step away from the spotlight:

He picked a place that felt like the opposite of everything he’d been living.

St. Andrews Bay—quiet, remote, full of potential—was exactly that.

Why He Moved Here

Clark’s move wasn’t random. It was calculated in the way practical men calculate:

Opportunity: West Florida was still frontier-like, but it wasn’t empty. It was a place where a determined person could shape outcomes.

Position and purpose: He held federal responsibilities connected to the region, and that gave him reason to be here beyond retirement.

Land and self-sufficiency: The bay promised the kind of life a former governor could build—property, production, and influence without the constant grind of elections and political enemies.

But more than anything, he came because he saw what St. Andrews Bay could become.

And he had the kind of mind that couldn’t sit in a beautiful place and do nothing with it.

Where He Put Down Roots

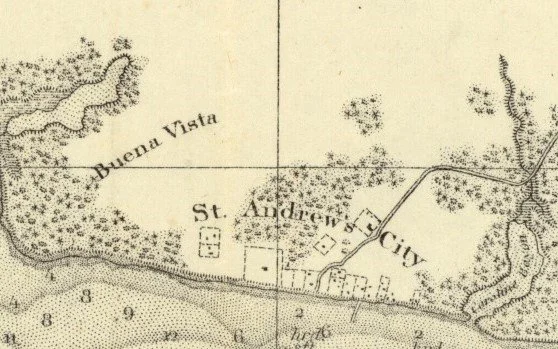

Clark chose a bluff overlooking the bay—high enough to catch the breeze, close enough to watch the water, and positioned where a settlement could naturally cluster.

In today’s terms, think Old Town St. Andrews—the historic core near the bay, not far from where the modern St. Andrews district gathers around its waterfront identity. His home was set on that elevated ground looking out across St. Andrews Bay, the kind of spot that still feels like “the right place” if you stand there and let your eyes follow the shoreline.

He built a substantial home for the era—more than a cabin, more than a camp. It was a statement:

This isn’t temporary.

And when one serious household plants itself in a place like this, others follow. That’s how towns begin—not with city charters and plaques, but with the first person who decides to stay.

How He Turned Camps Into a Community

Clark’s greatest skill wasn’t just leadership. It was institution-building.

He knew how to create the things that make a settlement “real”:

Stability: A permanent household, workers, and production meant the bay wasn’t just seasonal anymore.

Gravity: His presence attracted other settlers—people willing to build nearby because someone important had already done the hardest thing: committing first.

Credibility: A former governor living on St. Andrews Bay changed how outsiders talked about the place. It wasn’t just a backwater shoreline anymore—it was a place worth noticing.

He also helped support early community efforts, including education. We won’t camp out there too long, but it matters because it shows intent: Clark and his circle weren’t trying to survive day-to-day—they were trying to build something that could last beyond them.

Education is one of those “town” behaviors. Camps don’t build schools. Communities do.

The Mark He Left

Clark’s impact wasn’t a single building or one business. It was more fundamental than that:

He helped St. Andrews become a permanent settlement.

That sounds simple until you really think about it. Permanence is the hardest thing a frontier place can earn. It means enough people believe the future is worth investing in. It means families. Land claims. Trade patterns. Regular arrivals. Someone keeping records. Someone caring what happens next year.

Clark helped tip St. Andrews over that line.

And even after his death, the fact that St. Andrews had already become a real settlement meant it could keep growing without needing to be “re-founded” again.

After Clark: The Long Walk Toward the Civil War

John Clark died in 1832 of yellow fever, and like many early founders, he didn’t live to see what his first steps would eventually become.

After his death, St. Andrews didn’t explode into a boomtown. It wasn’t that kind of place yet. Growth came the old-fashioned way—slow, practical, shaped by the bay and the limits of frontier Florida.

The settlement that Clark anchored continued to attract people connected to the same coastal economy that still defines this area’s “salty” backbone:

fishing and seafood work

small-scale trade and shipping

salt production and preservation work

timber and the first movements of industry in the region

This was the era when St. Andrews became recognizably a town—still small, still rough, but no longer temporary.

And then came the Civil War era, which hit coastal communities like St. Andrews hard. The bay that had once been an economic advantage became a vulnerability. Saltworks, fishery operations, and waterfront activity—things that made places like St. Andrews useful—also made them targets.

The town would endure fire, disruption, and decline through that period.

But here’s the key point:

St. Andrews endured.

And that endurance only mattered because Clark had helped make it a real community in the first place. A camp can vanish without a trace. A town gets rebuilt.

His Lasting Legacy in Today’s St. Andrews

When you walk modern St. Andrews—the waterfront vibe, the sense of place, the stubborn pride, the feeling that this community has been through things and come back anyway—you’re walking on a foundation laid early.

John Clark’s legacy isn’t “a Clark building” you can point at.

It’s this:

St. Andrews became permanent when permanence wasn’t guaranteed.

The bay became a hometown, not just a work site.

Old Town became the seedbed for everything that came later—good years, hard years, rebuilding years.

He didn’t create the salty spirit. The bay did that.

But he did something just as important:

He helped give that spirit a place to live long-term—a settlement that could survive the centuries of change that followed.

And in St. Andrews, survival is a kind of success.

Addendum: Where His House Stood—and What Became of It

John Clark didn’t just choose St. Andrews in principle.

He chose it in geography.

He built his home on elevated ground overlooking St. Andrews Bay, in what is now known as Old Town—near the modern intersection of Beach Drive and Frankford Avenue. It was a deliberate location: close enough to the water to stay connected to the bay’s daily life, high enough to catch the breeze, located with a view of the entrance to St Andrews Bay, solid enough to anchor a settlement. Even now, if you stand in that area and look toward the bay, it still feels like the right place to begin a town.

Clark’s house was substantial by frontier standards. Contemporary accounts describe a large, two-story log structure, roughly sixty feet long, with massive fireplaces anchoring each end. This was not a temporary dwelling or a backwoods cabin. It was built to last, and to be used—not just as a home, but as a center of gravity for the growing settlement around it.

After Clark and his wife both died of yellow fever in 1832, the house outlived them. Like St. Andrews itself, it adapted. Ownership changed. The building was reportedly repurposed as a tavern or boarding house, serving travelers, workers, and locals as the town slowly grew along the bay. It remained part of the fabric of St. Andrews for decades—no longer the home of a former governor, but still a working part of the community he helped establish.

Sometime later, during the Civil War years, the house was lost—destroyed in the same period when St. Andrews became caught up in a broader coastal campaign tied to salt production and supply along the bay. That larger story deserves its own telling, and it’s coming next.

Today, nothing of the house remains above ground. Archaeological work in the area—particularly around the G.M. West House site—suggests later structures were built directly over the original footprint of Clark’s home. The ground absorbed the loss and moved on, as towns do.

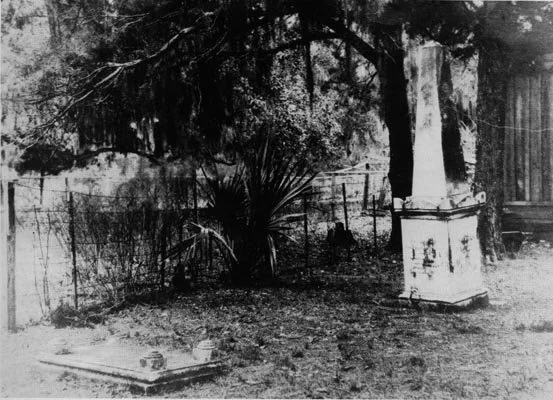

Clark and his wife were originally buried near the house, close to the place they had chosen as home. In 1923, their remains were moved to the Marietta National Cemetery in Georgia, returned at last to the state that defined much of his public life.

What remains in St. Andrews is not a building you can point to.

It’s the pattern he set.

A bluff chosen with intent.

A home built for permanence.

A settlement that endured—and came back anyway.

The house didn’t survive the century.

The town did.

And that, in St. Andrews, has always been the point.