Under Changing Flags

How Empires, Borders, and Ambition Shaped the Path of St. Andrews

St. Andrews didn’t grow up in a straight line. It grew up in the way old coastal places often do—pulled forward by faraway powers, pushed around by wars and treaties, and shaped as much by what didn’t happen here as by what did. Long before there were streets or storefronts, St. Andrews Bay was already known on maps, already useful, already fought over in the minds of people who had never stood on its shore. This is the story of how the Panhandle’s shifting ownership—and America’s restless expansion—quietly set the course for what St. Andrews would become.

Time Period: Spanish Naming and the Age of Empire (1500s–1763)

Long before towns existed here, St. Andrews Bay belonged on maps. Spanish cartographers marked safe water first—because a known harbor, even an unsettled one, was never invisible.

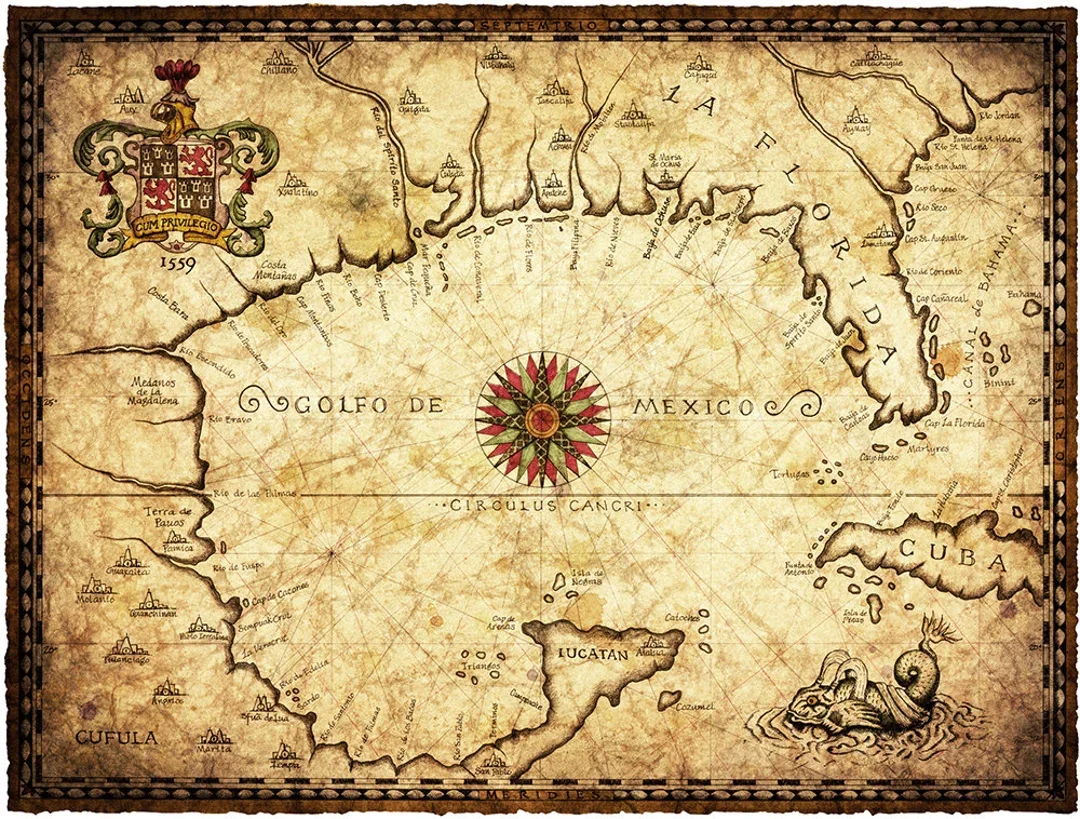

Credit

16th-Century Spanish-Style Map of the Gulf of Mexico

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

What was happening in the “New World” that mattered

Across the 1500s and 1600s, Europe treated North America like a chessboard. Spain, France, and Britain weren’t just exploring—they were staking claims, securing sea routes, and trying to control the wealth of a continent before anyone else could. The Gulf of Mexico wasn’t a backwater. It was a strategic highway.

What that meant for the Panhandle and St. Andrews

In this era, St. Andrews mattered more as a feature than a place. Spanish navigators named and recorded bays like this one because safe water and recognizable coastlines were priceless. A bay that could shelter ships—and be found again—belonged on a map even if nobody built a town beside it.

For the land itself, life followed older rhythms. People lived with the bay because the bay provided—food, travel routes, protection. But there was no European-style settlement that held. St. Andrews existed as geography and potential: a known harbor in an unknown coast.

The influence on St. Andrews’ future path

The first big influence on St. Andrews was simple: it was identified early and remembered. Once a place gets named and charted, it stops being invisible. And invisible places don’t become ports.

Time Period: British West Florida and the Revolutionary World (1763–1783)

When Britain divided Florida into East and West, power flowed toward Pensacola and established ports. St. Andrews Bay remained useful—but overlooked—beginning a long pattern of being just outside the center of imperial attention.

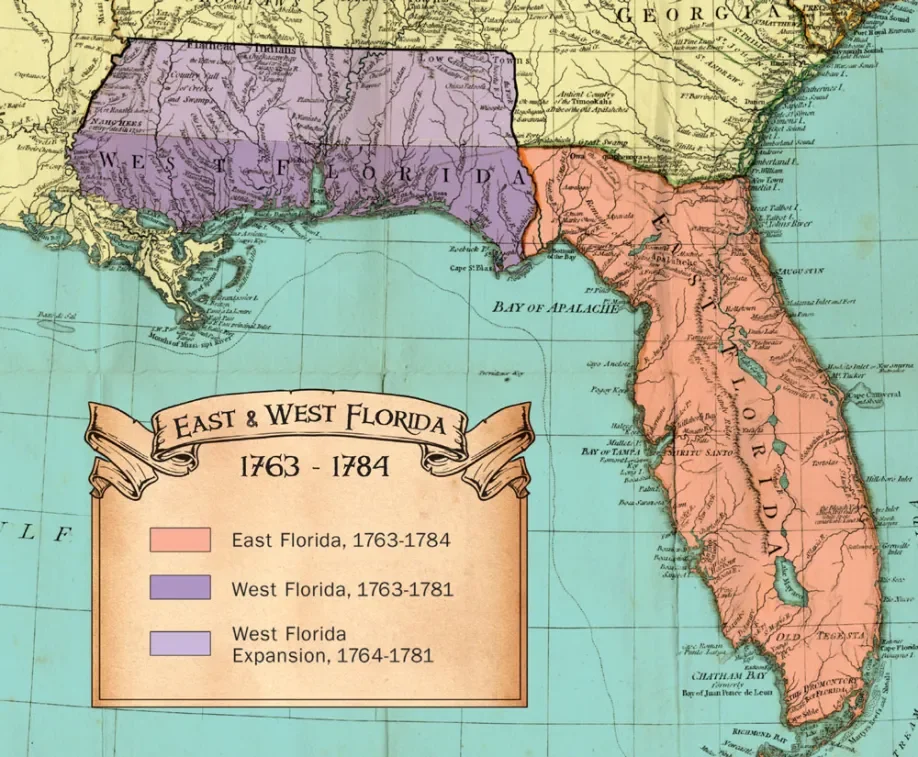

Credit

East & West Florida Map, British Period

Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

What was happening in the colonies that mattered

The mid-1700s were the era of imperial reshuffling. Britain emerged from the Seven Years’ War with expanded territory—and Florida became part of the British prize. But within a decade, Britain was facing a different problem: rebellion in the American colonies.

What that meant for the Panhandle and St. Andrews

Under Britain, Florida was split into East Florida and West Florida, with Pensacola as a key hub. Britain’s priorities were practical: control defensible ports, encourage settlement where possible, and make the territory pay for itself.

St. Andrews Bay still wasn’t the main act. The focus stayed on places already plugged into military and trade networks. St. Andrews remained valuable as a coastal asset, but it wasn’t where officials or investors placed their bets.

The influence on St. Andrews’ future path

Here’s the subtle lesson: St. Andrews spent its early centuries as a place that was useful but overlooked. That “almost important” status would echo later—especially once railroads and big money arrived in the Panhandle and chose winners and losers.

Time Period: Spain Returns, America Expands, and Borders Start Moving (1783–1821)

The Adams–Onís Treaty didn’t just transfer Florida—it stabilized a coastline that had lived under changing claims for centuries. Once borders stopped moving, places like St. Andrews could finally imagine permanence.

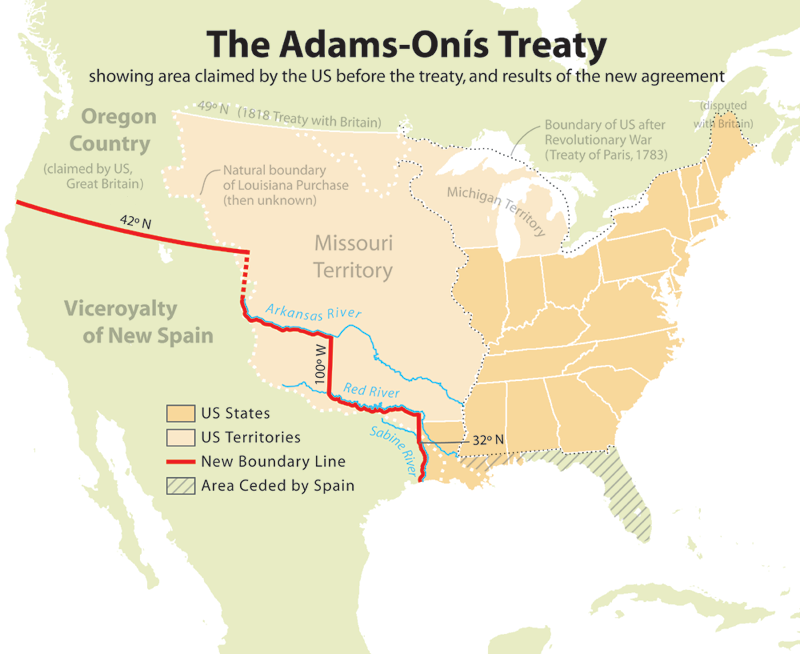

Credit

“Adams–Onís Treaty Map”

Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

What was happening in the young United States that mattered

After the American Revolution, the United States did what young, confident nations do: it started pushing outward. Population grew. Trade grew. Hunger for land grew. The Gulf Coast became strategically important—not just for defense, but for commerce. If the U.S. wanted security and shipping strength, it needed control of the coastline.

What that meant for the Panhandle and St. Andrews

Spain regained Florida in 1783, but it was a looser grip than before. Spain held Pensacola and the formal claim—but reality on the frontier was messy. Anglo-American settlers pushed south and west. Smuggling and informal trade thrived. And the idea that Florida was destined to be American territory became less a question and more a timeline.

Treaties started drawing lines. The border at the 31st parallel mattered because it signaled something bigger: Spain was negotiating, not commanding. The U.S. was not just a neighbor—it was a pressure force.

For St. Andrews, this period begins to hint at human footholds that feel familiar. Coastal living and bay-based survival were constant: fishing, small trade, early salt-making, and scattered settlement around nearby waters. Names appear in the record like early markers—people living around North Bay before St. Andrews was truly “a town.”

Key people and forces

Diplomats and treaty-makers in distant capitals shaped life here more than local leaders could:

Adams and Onís, negotiating what becomes the treaty that transfers Florida.

The broader U.S. political class pushing the nation’s borders outward.

On the ground, early settlers along the bays and inland waters were the human bridge between “mapped bay” and “lived community.”

The influence on St. Andrews’ future path

This era set the second major influence: St. Andrews would develop when the larger political map finally stabilized.You can’t build a permanent future if your flag might change next season.

Time Period: Florida Becomes American Territory and St. Andrews Finally Takes Root (1821–1845)

As the United States absorbed Florida, the Panhandle shifted from imperial edge to American frontier. This was the moment when mapped bays began turning into lived communities—including the first permanent roots at St. Andrews.

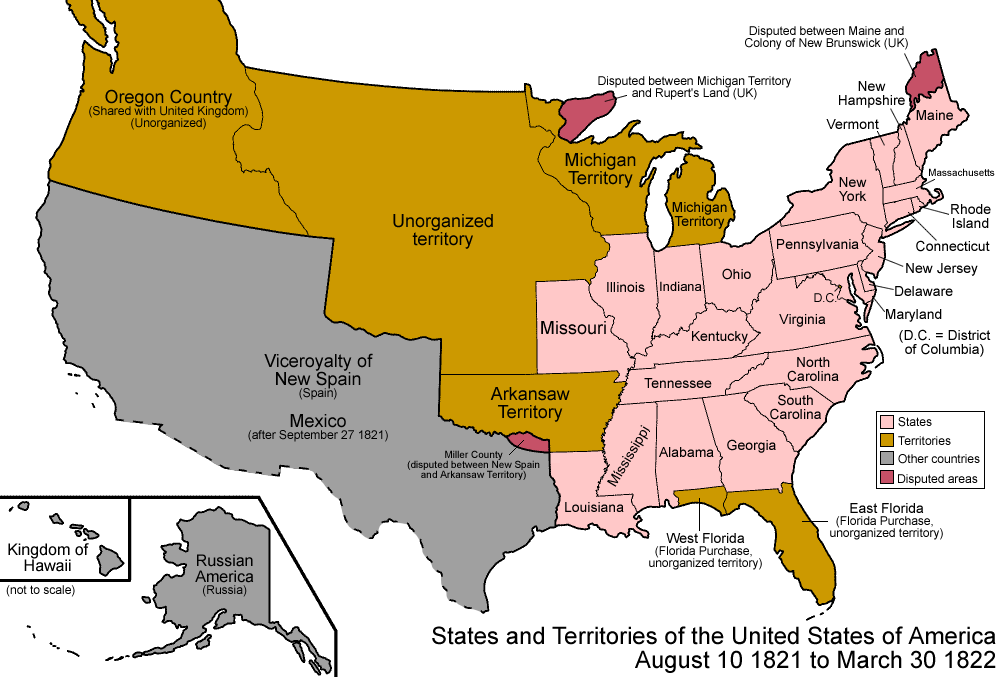

Credit

“States and Territories of the United States, 1821–1822”

Wikimedia Commons

Public Domain

What was happening in the United States that mattered

The early 1800s were the era of American momentum—new territories, new states, new roads, and a national obsession with expansion. The U.S. was turning geography into governance. Land was being surveyed, organized, sold, settled, and defended.

Florida’s transfer to the United States wasn’t just a paperwork event—it was the start of American systems arriving: territorial government, courts, land claims, and the slow transformation from frontier margin to organized place.

What that meant for the Panhandle and St. Andrews

Florida becomes a U.S. territory, and the Panhandle begins its shift from imperial edge to American frontier.

And now St. Andrews changes from potential to presence.

By the late 1820s, St. Andrews Bay has a small but real cluster of settlers. A familiar St. Andrews pattern begins: not a boomtown rush, but a cautious rooting-in—people who come because the bay offers what it has always offered: a living.

One name matters above the rest in this early chapter: John Clark. He didn’t just visit. He built. He anchored. He helped turn “the shore of a bay” into something that could become a community. In Stories of St. Andrews terms, he’s one of those figures who appears at exactly the right moment—when the wider world finally made local permanence possible.

The early “salty” economy (before the big modern drivers)

St. Andrews wasn’t built first on railroads or resorts. It was built on old, reliable coastal work:

Fishing

Salt-making

Boarding and hosting visitors drawn to the bay

Nothing glamorous—just the honest work of turning water, wind, and shoreline into survival. The kind of foundation that doesn’t make headlines but makes towns.

The influence on St. Andrews’ future path

This period sets the third major influence: St. Andrews’ earliest growth was bay-driven, not inland-driven. That distinction matters later—because when inland infrastructure (especially rail) arrives in the Panhandle, it doesn’t automatically favor a town whose identity and economy are tied to the water.

Time Period: Statehood and the Long Shadow of Early Choices (1845)

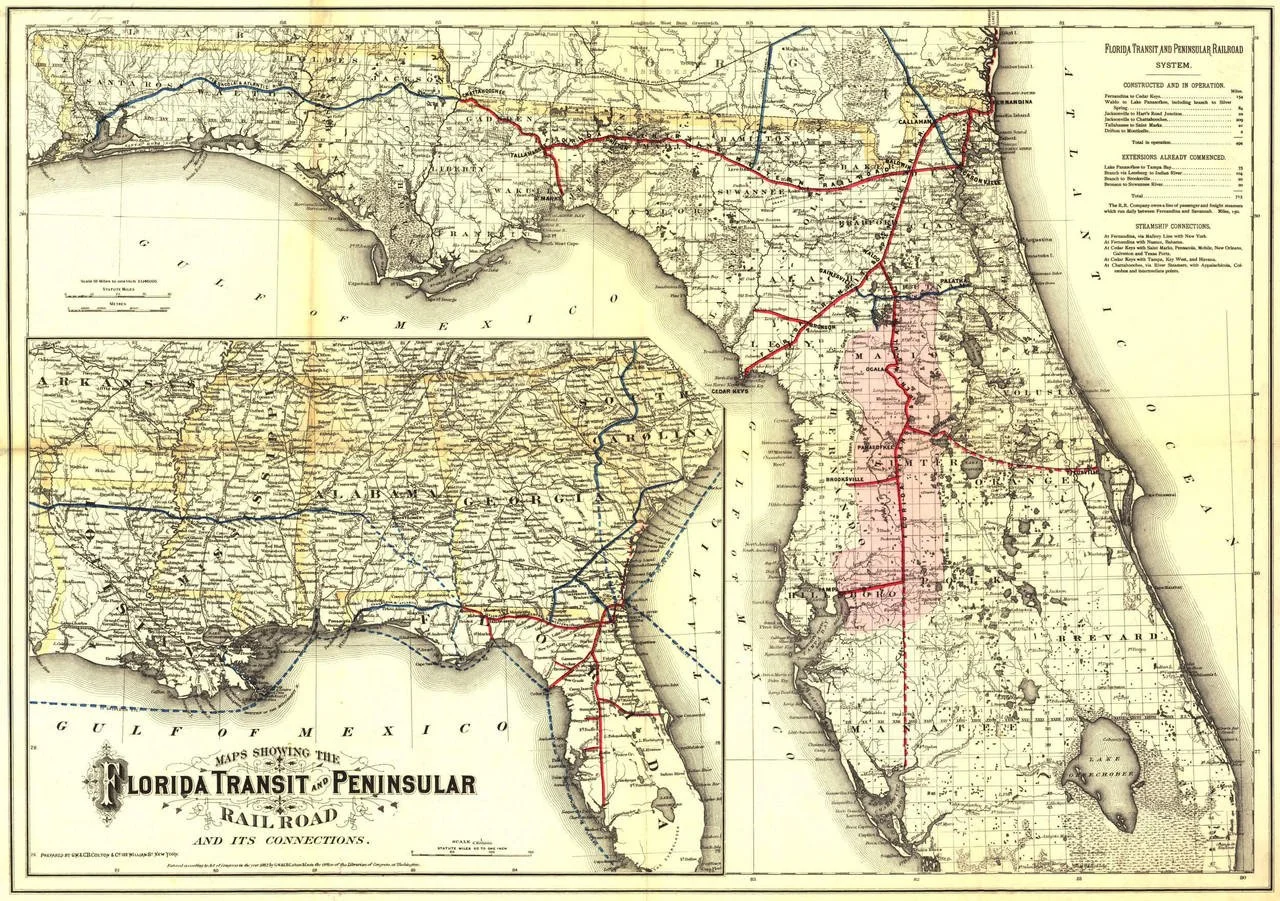

By the late 19th century, Florida’s future was being redrawn by steel rails instead of shifting flags. Railroad maps like this one reveal which places were chosen to grow—and which, like St. Andrews, would remain defined by the water rather than inland infrastructure.

Credit

Florida Transit & Peninsular Railroad Map, c. 1882

Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division

Public Domain

What was happening nationally that mattered

By the time Florida becomes a state, the United States is accelerating into a new phase—more population, more commerce, and more intense competition over which places will become regional centers. Statehood is not the end of the story, but it’s the end of the “unstable ownership” era.

What that meant for St. Andrews

Statehood doesn’t instantly transform St. Andrews—but it locks in the framework. From here forward, St. Andrews will rise or fall less on whose flag flies and more on the harder question: where will the big development currents flow?

That’s where the Panhandle’s later story begins—railroads choosing routes, ports competing, industries clustering. But the seed of that later drama is planted here: St. Andrews is now a true place, but it is still a small coastal community in a region where future growth will increasingly be decided by infrastructure and investment.

The influence on St. Andrews’ future path

Statehood cements the final influence of this chapter: once the political map stops shifting, the economic map starts shifting faster. And St. Andrews will spend the next generations proving it can keep its identity even when bigger forces try to redraw its destiny.

What This Whole Era Explains About St. Andrews

If you want one takeaway theme—one thread that ties the whole story together—it’s this:

St. Andrews was shaped first by being known, then by being overlooked, and finally by becoming permanent just as America began choosing which places would become power centers.

It was named early—so it stayed on the map.

It was not prioritized by empires—so it avoided early overdevelopment but also missed early advantages.

It took root when the U.S. made Florida stable—built on bay-work, not inland industry.

And it entered statehood as a community with a strong coastal identity—one that would later have to survive the hard reality of being near bigger, louder growth engines.

Which, honestly, is a pretty good origin story for a town that still prides itself on being independent, salty, and stubborn in the best way